[Since early 2018 I have given a number of public and academic talks on Robots Thinking Fast and Slow. All the illustrations in this post are taken from the slide decks accompanying these talks.]

Recent advances in AI technology have built significant excitement as to what our robots may be able to do for us in the future. Progress is truly inspirational. But where, you may ask, are the robots? Why can I buy a voice assistant but not a robust and versatile household robot? The answer lies in the fact that embodiment - the notion of a physical agent acting and interacting in the real world - poses a particular set of challenges. And opportunities.

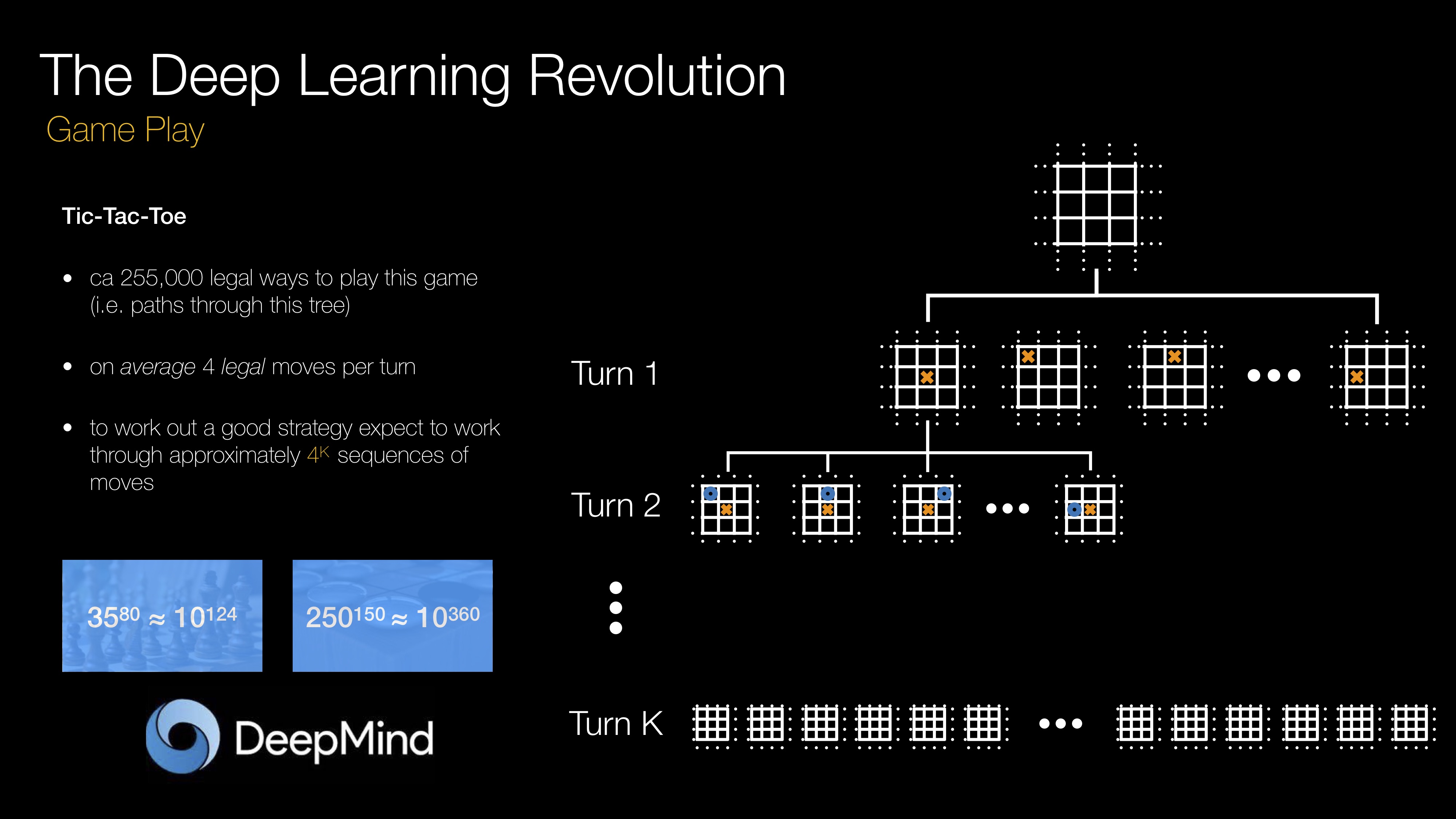

Machines are now able to play Atari, Go and StarCraft. However, success here relies on the ability to learn cheaply, often within the confines of a virtual environment, by trial and error over as many episodes as required. This presents a significant challenge for embodied agents acting and interacting in the real world. Not only is there a cost (either monetary or in terms of execution time) associated with a particular trial, thus limiting the amount of training data obtainable, but there also exist safety constraints which make an exploration of the state space simply unrealistic: teaching a real robot to cross a real road via trial and error seems a far-fetched goal. What’s more, embodied intelligence requires tight integration of perception, planning and control. The critical inter-dependence of these systems coupled with limited hardware often leads to fragile performance and slow execution times.

In contrast, we require our robots to robustly operate in real-time, to learn from a limited amount of data, make mission- and sometimes safety-critical decisions and occasionally even display a knack for creative problem solving.

A Dual Process Theory for Robots

Cognitive science suggests that, while humans are faced with similar complexity, there are a number of mechanisms which allow us to successfully act and interact in the real world. One prominent example is Dual Process Theory, popularised by Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow. Dual Process Theory postulates that human thought arises as a result of two interacting processes: an unconscious, involuntary - intuitive - response (System 1) and a much more laboured, deliberate reasoning (System 2). Our ability to assess the quality of our own thinking - our capacity for metacognition - plays a central role.

If we accept that Dual Process Theory plays a central role in our own interactions with the world, the notion of exploring a similar approach for our robots is a tantalising prospect. If we can establish a meaningful technology equivalent - a Dual Process Theory for robots - mechanisms already discovered in the cognitive sciences may cast existing work in new light. They may provide useful pointers towards architecture components we are still missing in order to build more robust, versatile, interpretable and safe embodied agents. Similarly, the discovery of AI architectures which successfully deliver such dual process functionality may provide fruitful research directions in the cognitive sciences.

While AI and robotics researchers have drawn inspiration from the cognitive sciences pretty much from the outset, we posit that recent advances in machine learning have, for the first time, enabled meaningful parallels to be drawn between AI technology and components identified by Dual Process Theory. This requires mechanisms for machines to intuit, to reason and to introspect - drawing on a variety of metacognitive processes. Here we explore these parallels.

Machine Learning, Intuition and Reasoning

Machine learning is essentially an associative process in which a mapping is learned from a given input to a desired output based on information supplied by an oracle. We use the term oracle here in its broadest possible sense to refer to both inductive biases and supervisory signals in general. In a brazen break with standard deep learning terminology, we also refer to an oracle’s knowledge being distilled into a machine learning model. And we take as a defining characteristic of an oracle that it is in some sense resource intensive (e.g. computationally, financially, or in terms of effort invested).

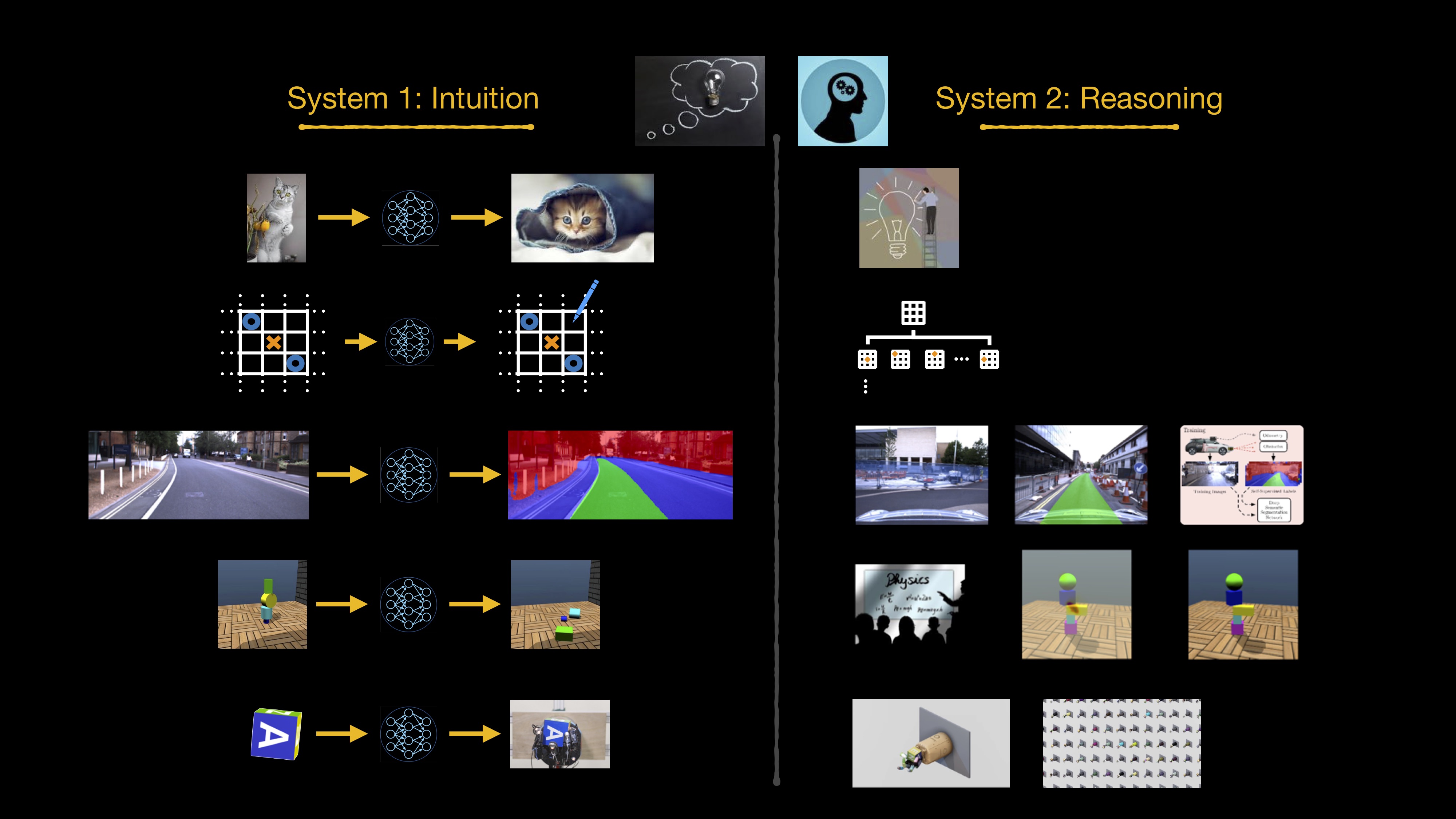

The learning of mappings of inputs to outputs has, of course, been a theme in ML for decades. However, in the context of Dual Process Theory, the advent of deep learning has afforded our agents principally two things:

- an ability to learn arbitrarily complex mappings; and

- an ability to execute these mappings in constant time.

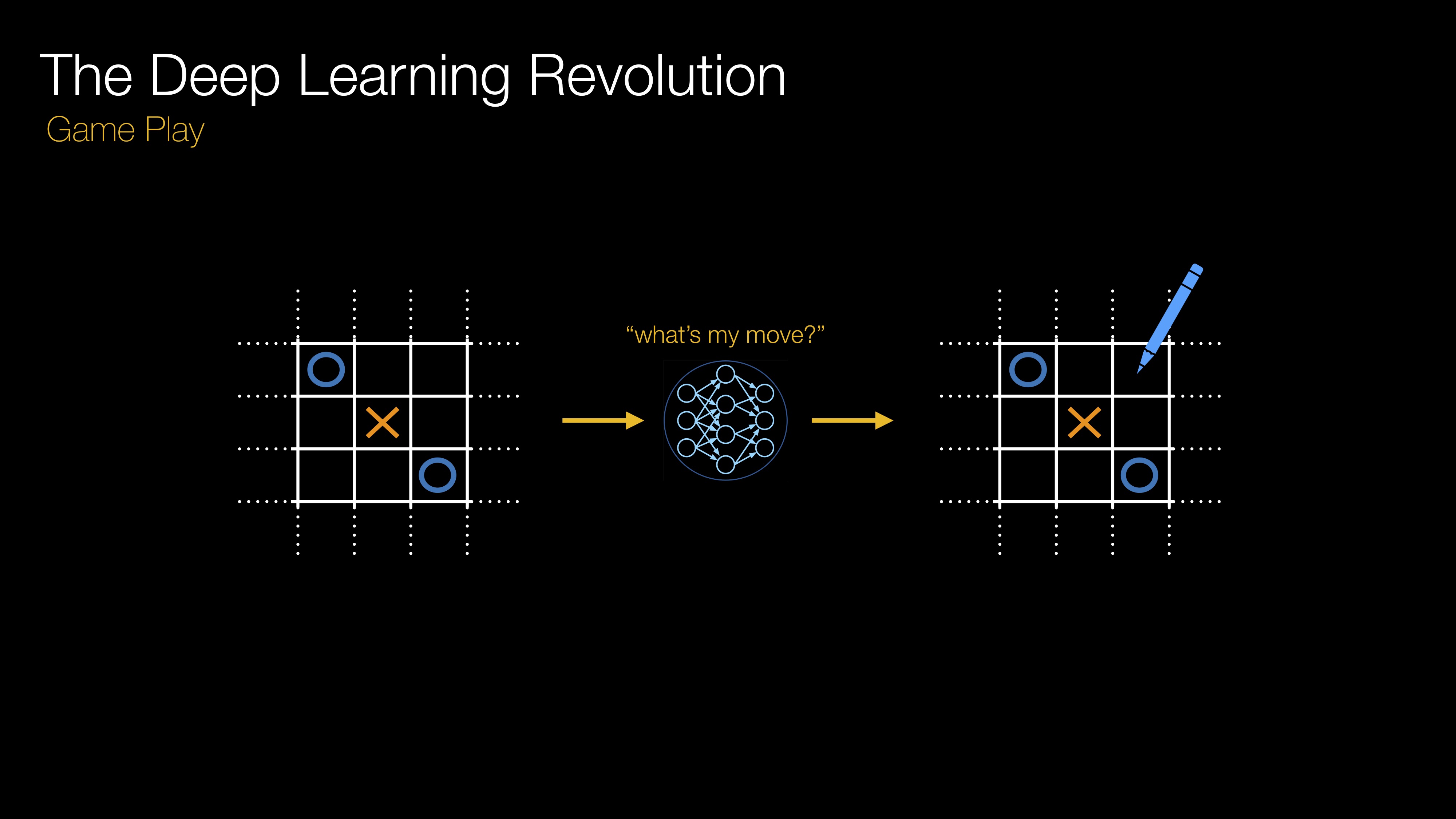

Consequently, by learning ever more complex mappings from increasingly involved oracles we now routinely endow our agents with an ability to perform complex tasks at useful execution speeds. In the view offered here, for example, DeepMind’s AlphaGo distils knowledge from Monte Carlo Tree Search (the oracle) and self-play into a model which predicts value and next move given a particular position. (The connection between neural network models trained using MCTS and more generally in a reinforcement learning context and the Fast and Slow paradigm has not gone unnoticed. It is the subject, for example, of this post by David Barber and the accompanying paper as well as in this recent TICS paper by DeepMind.) Another example is OpenAI’s Learning Dexterity project, which distils knowledge from reinforcement learning (essentially trial and error) using domain randomisation (the combined oracle) into a model which can control a Shadow Hand to achieve a certain target position in a dexterous manipulation task.

Figure 1: an illustration of game play inspired by DeepMind’s AlphaGo series [top row] and the Learning Dexterity project published by OpenAI in 2018 [bottom row] enabled by deep learning. On the left is an introduction to the application, the middle column gives a flavour of the oracle and the right illustrates the model which captures the oracle’s knowledge. (Click to enlarge.)

But we can take an even broader view of what constitutes an oracle. Figure 2 shows an example of hundreds of person hours of systems engineering being distilled (via the automatic generation of training data) into a machine learning model, which predicts where a human might drive given a particular situation (see Path Proposals for details). Another increasingly common application is the learning of intuitive physics models in which the outcome of a particular scenario is predicted by a model trained on data arrived at through physical simulation. The ShapeStacks study, for example, amongst other things determines whether a particular toy block tower is stable or otherwise. It does so by training a neural network model on image data generated using a physics simulator - thus implicitly encapsulating knowledge of the physical world.

Figure 2: a system predicting where a human might drive in a particular situation as described in this paper on Path Proposals [top row] and an intuitive physics application as described in ShapeStacks, in which a model learns to predict the stability of a block tower based on physical simulations [bottom row]. As before, on the left is an introduction to the application, the middle column gives a flavour of the oracle and the right illustrates the model which captures the oracle’s knowledge. (Click to enlarge.)

Faced with an image of a block tower, we do not tend to write down the laws of physics and analyse the particular setup. We have a gut-feeling, an intuitive response. Importantly, owing to their ability to mimic the expertise of an oracle in a time (or generally resource) efficient manner, one might view the execution of a neural network model as analogous to an intuitive response. And of course we also have accesss to a (very) broad class of oracles, which we might (generously perhaps, but with artistic license) refer to as reasoning systems. These then constitute analogues to System 1 and System 2. A Dual Process Theory for robots has thus firmly moved within reach.

Figure 3: A Dual Process Theory for Robots

Many of the failure modes of modern machine learning systems are associated with a lacking ability to know when they don’t know. Consequently, attempts at remedying this shortcoming have received much attention over the years. Yet inference remains notoriously over-confident in many cases of interest. Theoretical bounds are often too loose. And the assumption of independent, identically distributed training and test data is routinely violated - particularly in robotics (see, for example, here or here). Astonishingly, much the same could be said about humans. We are notoriously bad at knowing when we don’t know. And we operate in significantly non-stationary (in the statistical sense) environments. Yet - we do operate. Much of this success is commonly attributed to our metacognitive abilities: the process of making a decision, the ability to know whether we have enough information to make a decision and the ability to analyse the outcome of a decision once made.

One of the interesting aspects of a Dual Process Theory for robots is the fact that - given the analogy holds - metacognition finds a natural place in this construct: it bridges the two systems by regulating the intuitive, almost involuntary response of System 1 with a supervisory, more deliberate one of System 2. Don’t trust your intuition, think about it. But only where appropriate, which is really the crux of the matter. Failure (or deliberate deception) of this mechanism is, of course, what gives rise to the cognitive biases now so well described in the literature. Examining research on metacognition, therefore, might shed new light on how to tackle the knowing when you don’t know challenge. And as an added bonus we now get machines with their own cognitive biases.

In Thinking Fast and Slow Kahneman exemplifies the responsibilities of System 1 and System 2 with a number of simple questions. For example, what is 2 + 2? Or what is 2342114 ÷ 872? The former elicits a System 1 response (a recall operation). The latter triggers the need for pen and paper - deliberate reasoning (System 2). Interestingly, one of the mechanisms regulating this routeing - or algorithm selection - has been identified by metacognition researchers as the Feeling of Knowing Process (the interested reader is referred to this research review). It is executed near instantaneously and is able to make an (in the majority of cases) appropriate choice even based on only parts of the question - so by the time you have heard “2 +” your brain will have decided that you likely already know the answer to the question and only need to retrieve it.

Consider this in the context of robotics. And let us conjecture that the Feeling of Knowing Process is itself an intuitive (System 1 -like) response. This immediately points at a set of now viable technical approaches in which, for example, the outcome of a downstream system (either in terms of success/failure or in terms of confidence in outcome) given a particular input is distilled into a machine learning model (NB: statistical outlier detection also falls into this category). Such performance predictive models are now relatively common-place in the robotics literature. They are used, for example, to predict the performance of perception systems (e.g. see here or here) or vision-based navigation systems (e.g.here). They can even be leveraged to distil the computationally expensive dropout sampling in the forward pass of a neural network for epistemic uncertainty estimation into a predictive model as done in this work.

While distilling performance into a machine learning model is one way of giving a machine a Feeling of Knowing, we do not propose that it is the only - or even the optimal - way. Feeling of Knowing is, in fact, not the only process involved in metacognition. The extent to which it can be used and the mechanisms to best integrate it into our AI architectures are, as yet, unknown. However, one exciting aspect of a Dual Process Theory for robots is that there now exists a tantalising avenue within which to contextualise and along which to direct research.

Towers Built on Intuition

As a final thought for this post we offer a view of this distillation process as the ability, in the System 1 and System 2 analogy, to transition from one system to the other via deliberate, effortful practice. Consider a toddler learning how to stack blocks such as the one on the left in Figure 4. When she is more experienced we might reasonably expect her to simply stack objects almost without thinking about it (an intuitive response). Were a machine to go through a similar process it might look like the trial-and-error experiment in the middle pane in Figure 4, which is also part of the ShapeStacks study. Here different shapes are tried in different orientations as to how well they support a building block (green = good, red = bad). This gives rise to a sense of stackability for particular block geometries.

Figure 4: Practising to stack. (Click to enlarge.)

Combining a sense for stackability with that for stability mentioned above leads to an intuitive and scalable way in which towers are built: pick the next most stackable item in its most stackable pose and place it such that the overall construct looks stable (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Stacking based on two intuitions.

In this post we have ventured to establish an analogy between the building blocks of Dual Process Theory and some of the tools in machine learning and AI technology that are now available to us. The emergence of a Dual Process Theory for robots may open up a number of research challenges and directions worth exploring in our endeavour to build more robust, versatile, interpretable and safe embodied agents. Of course, the links we have highlighted here are but a few selected views on how such an analogy may be established and where it might lead. But we do hope it provides inspiration and food for thought for the robotics and learning communities alike.

Notes

comments powered by